Retirement can mean different things to different individuals. For this blog, we’ll begin with its Oxford Dictionary definition: “the act of stopping work, usually due to reaching a certain age, and the time following when this happens.” This definition implies an expectation: one works until a certain age before stepping away. But why do we assume work must be tied to a specific age at all? If the purpose of work is to earn our bread, why don’t we have the freedom to decide how long we want to work? These questions led me to explore the origins of retirement and its historical context.

As I delved into the concept, it became clear that understanding retirement is incomplete without examining the meaning and purpose of work itself. After all, retirement is not just an end; it’s a reflection of how we view work, purpose, and life.

In this blog, I will uncover the history of retirement, what it has come to mean in our lives, and where we may have gone wrong. By exploring these ideas, I hope to inspire a rethinking of retirement—not as an end to work but as a beginning of something more meaningful.

History of retirement

The concept of retirement began in the late 19th century with Germany’s 1889 pension system under Otto von Bismarck, offering financial support to workers aged 65—then near life expectancy. Designed to address labor turnover and support aging workers in industrial jobs, it soon became a global model. However, this age-based system, rooted in a different era, no longer aligns with today’s longer lifespans and evolving views on work and purpose.

For example, in countries like Japan, where life expectancy is among the highest globally, many retirees are returning to the workforce in part-time roles. Programs like “Silver Human Resources Centers” reflect a shift in how retirement is approached—not as a complete halt to work but as a phase of flexibility and contribution.

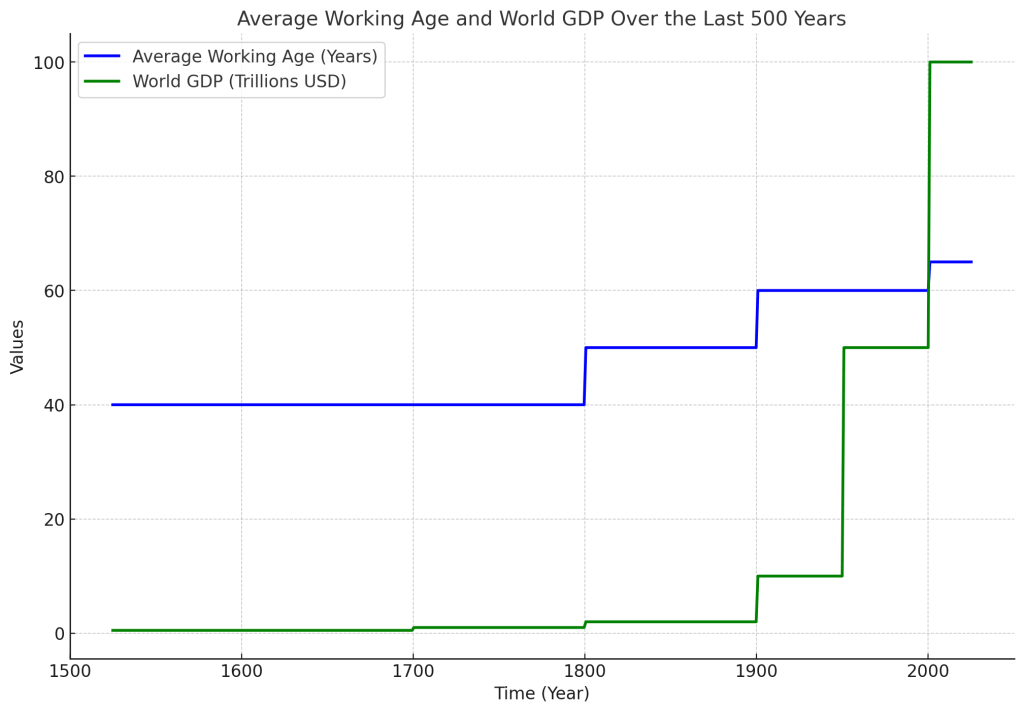

It is no coincidence that the world’s GDP and the average working age are increasing proportionally. The more we work, the more economic value we generate, but this is not without consequences.

What Is the Problem? All Good, Right?

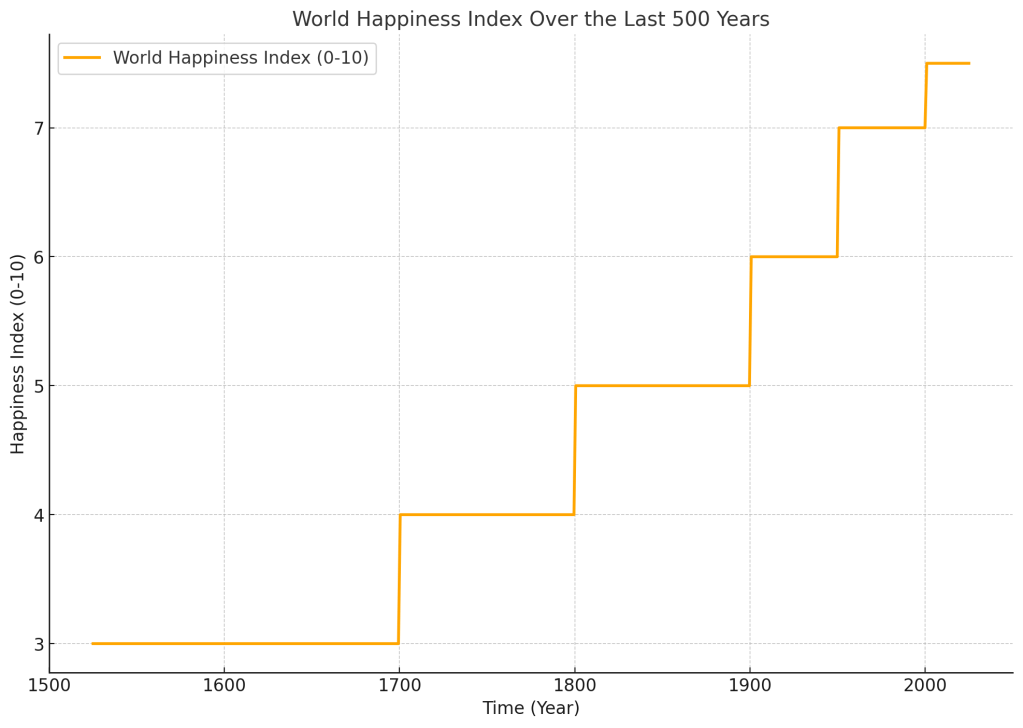

It is also no coincidence that the happiness index is increasing globally. There is no denying that work gives us a sense of purpose in life. However, the increase in happiness cannot be solely attributed to work; other factors like economic development, healthcare advancements, and societal freedoms also contribute. For instance, Scandinavian countries—often topping happiness indices—combine shorter workweeks with high-quality public services.

That said, an increase in the average retirement age has negatively impacted job satisfaction and work-life balance. In the U.S., surveys show that employees in their 50s and 60s report declining satisfaction with rigid work schedules, particularly when health or family responsibilities are at stake.

How Have Work Patterns Changed?

The Industrial Revolution initiated a profound transformation in work patterns. Before industrialization, most people were self-employed as farmers, craftsmen, or merchants. They enjoyed greater flexibility and autonomy in their work. For instance, a farmer could decide when to plow fields or tend to crops based on personal and seasonal needs, rather than adhering to an employer’s schedule.

However, industrialization introduced factory-based work, characterized by standardized hours and specialization. People flocked to cities, becoming employees subject to regimented schedules. This shift was pivotal in the emergence of retirement, as the structured and demanding nature of industrial work created a need for a defined phase to step away from labor.

Consider the 12-hour shifts in early factories during the 19th century. Workers often faced monotonous tasks with little room for creativity or autonomy. Retirement became a symbol of relief from such grueling conditions. Contrast this with today’s gig economy, where flexibility has reemerged but often at the expense of stability and benefits.

How Does This Affect Modern Work Culture?

The shift from self-employment to wage labor during the Industrial Revolution continues to influence modern work culture. For example, while tech companies offer creative freedom and flexibility, they also often demand high productivity. “Hustle culture” in startups mirrors factory work’s intensity but replaces physical labor with mental strain.

Some tech workplaces have embraced flexible schedules and remote work, allowing employees better work-life balance. For instance, companies like Atlassian and GitHub promote asynchronous work, giving employees control over their schedules. Yet, the pressure to deliver in high-stakes environments can still resemble the regimented demands of industrial labor.

Interestingly, the rise of entrepreneurship in the tech world reflects a return to the autonomy of pre-industrial work. Professionals starting their own ventures often cite a desire for independence, echoing the self-directed work of earlier eras.

What would an alien say, if he looked at us working all our life (until age of retirement) ?

“Why do you spend the majority of your finite existence trading time for resources, only to truly start living when your strength wanes? On our planet, we design systems to ensure life is lived meaningfully throughout, not just at the end.”

Rethinking Retirement

The current model of retirement is due for an overhaul. Instead of viewing retirement as a hard stop to working life, we can reimagine it as a transition into a phase of flexibility, learning, and contribution. Policies that encourage phased retirements, part-time roles for seniors, and financial literacy can help shift the narrative. Just as work has evolved over centuries, so too should retirement adapt to meet the needs of modern life.